In the quiet, early hours of the morning, while the city still slumbers, a certain group of people are already up, potentially reaping metabolic health benefits unknown to their night owl counterparts. A recent study focusing on a Ukrainian cohort sheds light on how being a morning person, or having a morning chronotype, correlates with healthier dietary patterns and improved metabolic parameters. This investigation into the interplay between our biological clocks and our health offers a fascinating glimpse into the potential for chronotype as a modifiable lifestyle factor in enhancing metabolic health.

The Early Bird Gets the Health Benefits

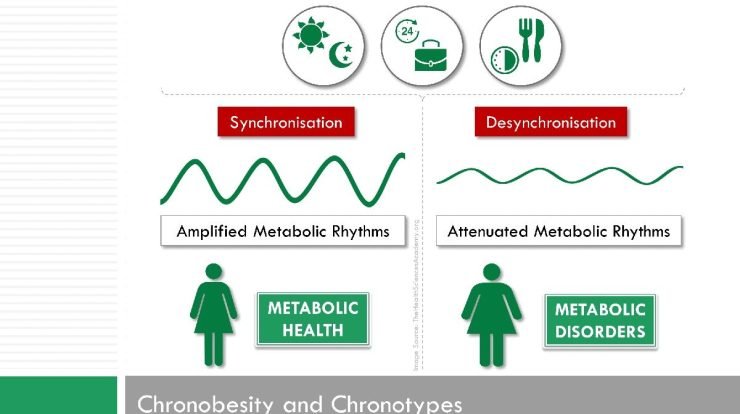

The study’s findings indicate that individuals with a morning preference tend to consume diets lower in fat and animal protein, coupled with an earlier last eating occasion. These dietary habits are associated with several improved metabolic health markers, including lower body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, fasting triglycerides, and glucose levels. Such associations persisted even after adjusting for age, sex, physical activity, and BMI. Interestingly, morning types also exhibited greater physical activity and a better alignment with their biological clock, as evidenced by lower social jetlag (SJL).

Challenging the Night Owl Lifestyle

While the study presents a compelling case for the metabolic advantages of being a morning person, it also acknowledges its limitations, such as its cross-sectional design, reliance on self-reported sleep and dietary data, and a relatively small sample size. These caveats underscore the need for further research to fully understand the mechanisms behind the observed associations and to establish causality. Nevertheless, this research contributes to the growing evidence suggesting that adjusting one’s chronotype could be a strategic approach to improving metabolic health.

Looking Forward: Tailoring Diets to Our Biological Clocks

The implications of this study are far-reaching, hinting at the potential for personalized dietary interventions based on individual chronotypes. Upcoming randomized controlled trials, such as those comparing a chronotype-adapted diet to a standard low-calorie diet, aim to further explore this possibility. These studies seek to optimize meal timing according to one’s peak metabolic periods, potentially offering a more personalized approach to managing weight and improving cardiometabolic health.

The concept of aligning our eating patterns with our internal clocks is not only a promising avenue for enhancing metabolic health but also a testament to the intricate connections between our lifestyle choices and our wellbeing. As we await the results of these pioneering trials, the current evidence invites us to reflect on our chronotypes and consider the role they might play in our overall health strategy.

Source link